1914: Then Came Armageddon

Navies of the Great War

“John Mackenzie… once remarked that the yacht was the most ‘damnable, wallowing, bucking, blistering craft I’ve ever laid eyes on… [a] misbegotten, misguided hunk of cheese’”.

Crisis at Sea: The United States Navy in European Waters in World War I. Page 313.

Varieties of Naval Vessels

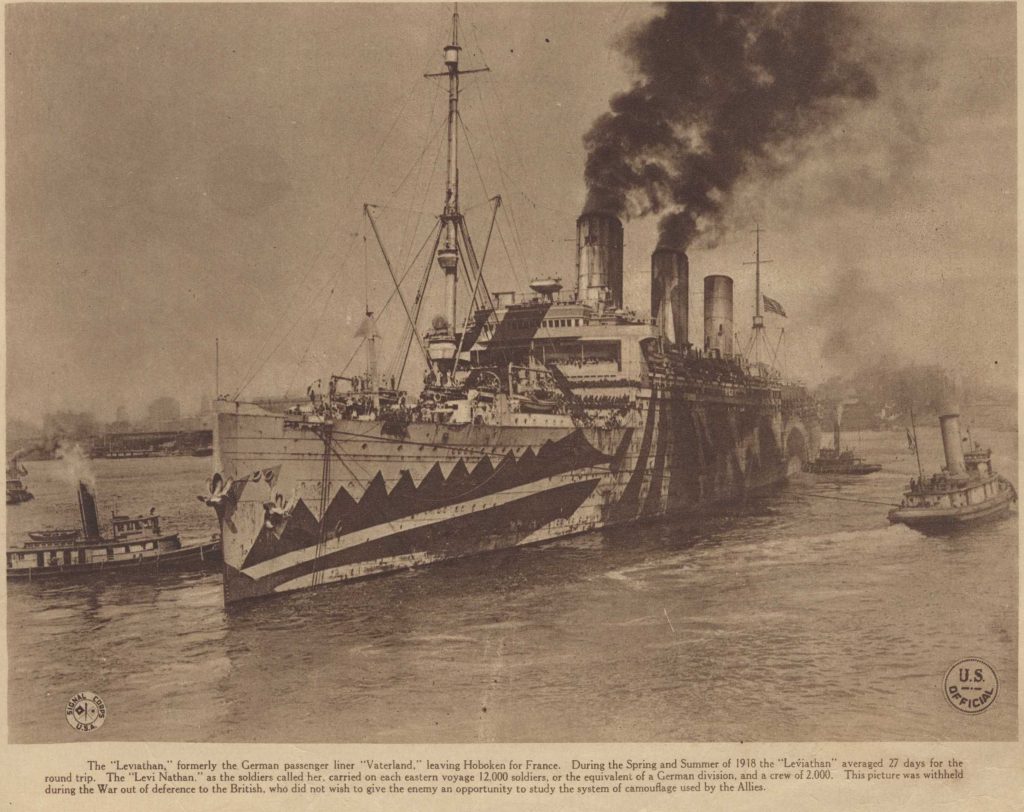

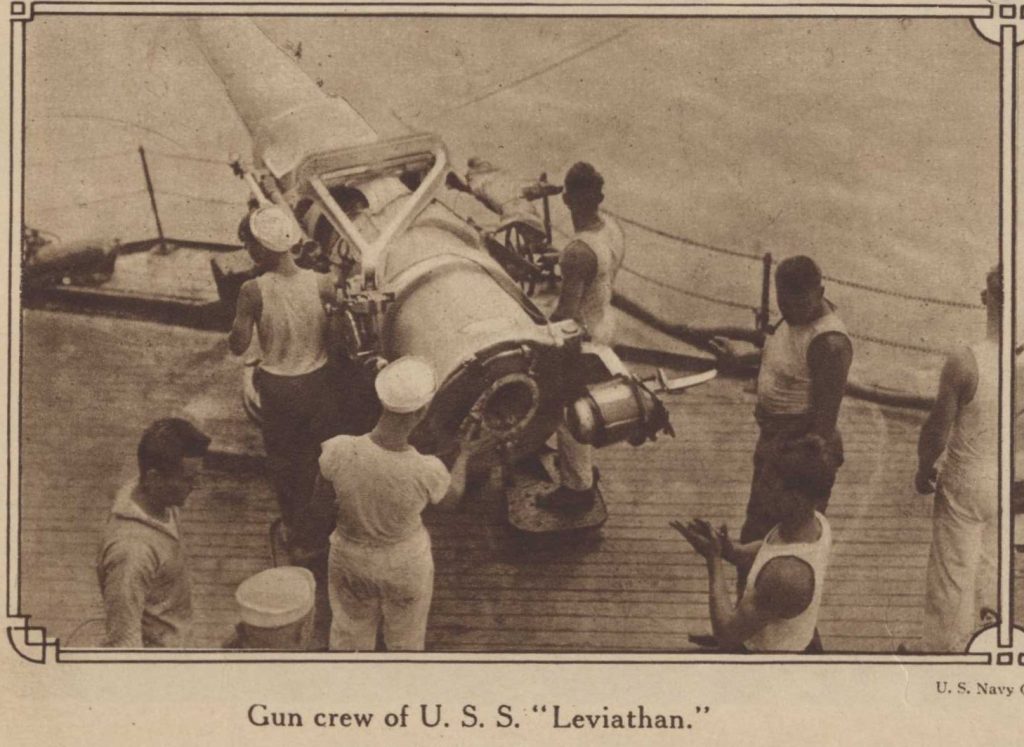

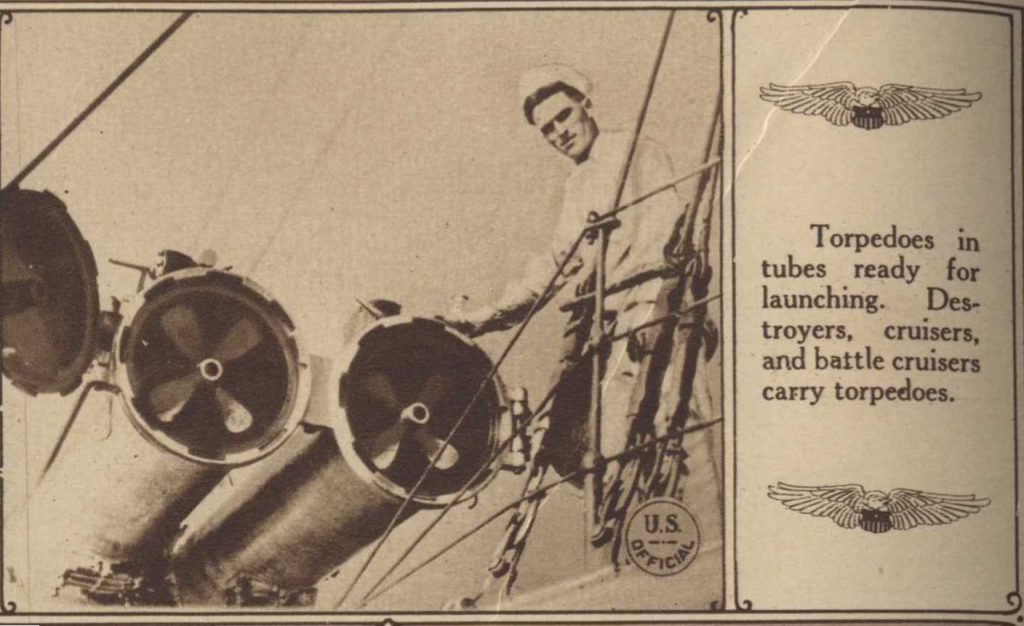

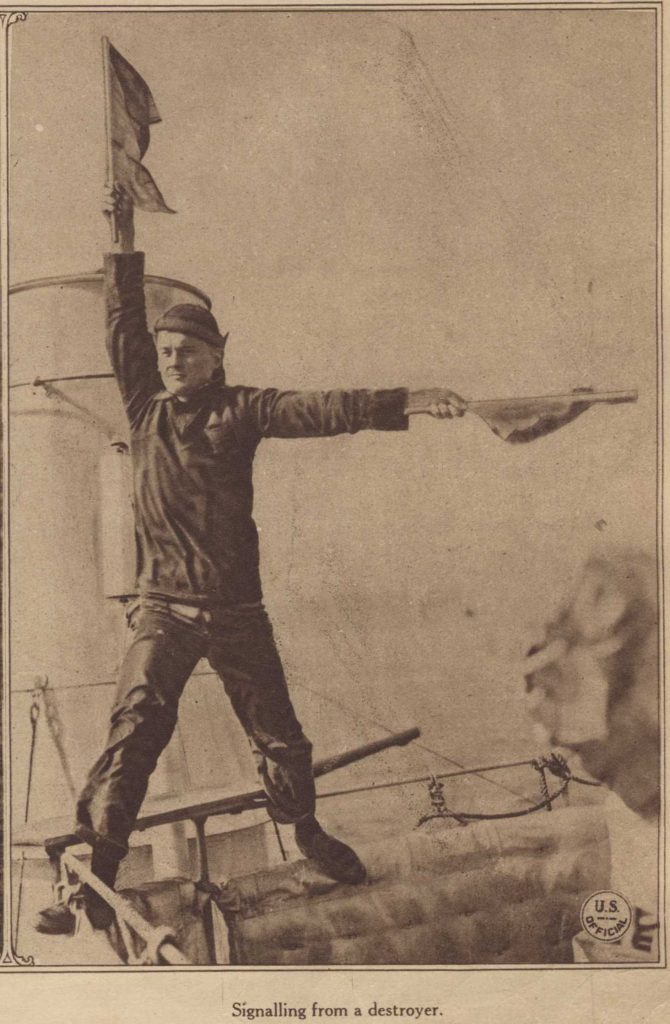

Many different vessel types were deployed during the Great War. Some of the most well-known were the German U-boats that sparked terror through their use of unrestricted submarine warfare, the practice of attacking any enemy vessel regardless of whether it was a civilian or military ship. Naval destroyers were one of the most important types of vessels in the war due to their ability to inflict damage through their heavy mounted guns and highly technical aiming systems. (Warships 77). Many countries, including Germany and the United States commandeered civilian ships to be used in service. These civilian ships, including yachts and merchant ships, were used for various military tasks, such as mine-laying or the escort of important political figures. For American soldiers, despite the luxury, being assigned to a yacht was often ultimately a disappointment because they were unfit for naval combat (Still 313). As for the number of American ships built during the war “the [United States] Navy added 208 ships – 87 private yachts, 39 tugboats, 8 tankers, 50 merchant ships, 12 passenger liners, and 12 fishing boats… By the war’s end, the Navy boasted 774 commissioned ships” (Still 307). These numbers are a representation of total warfare as suggested by the Navy Department and Congress’s official recommendation of “As many [scout destroyers] as possible” to be made in 1917 (Besch 5). To put this in perspective, in 1897 Germany released plans to build at least ninety-seven new ships under the guise of “commercial considerations” and constructing “a political power factor which England could not ignore” (Padfield 41). Effectively, the United States, while at war, doubled the peace time ship construction of Germany.

Training

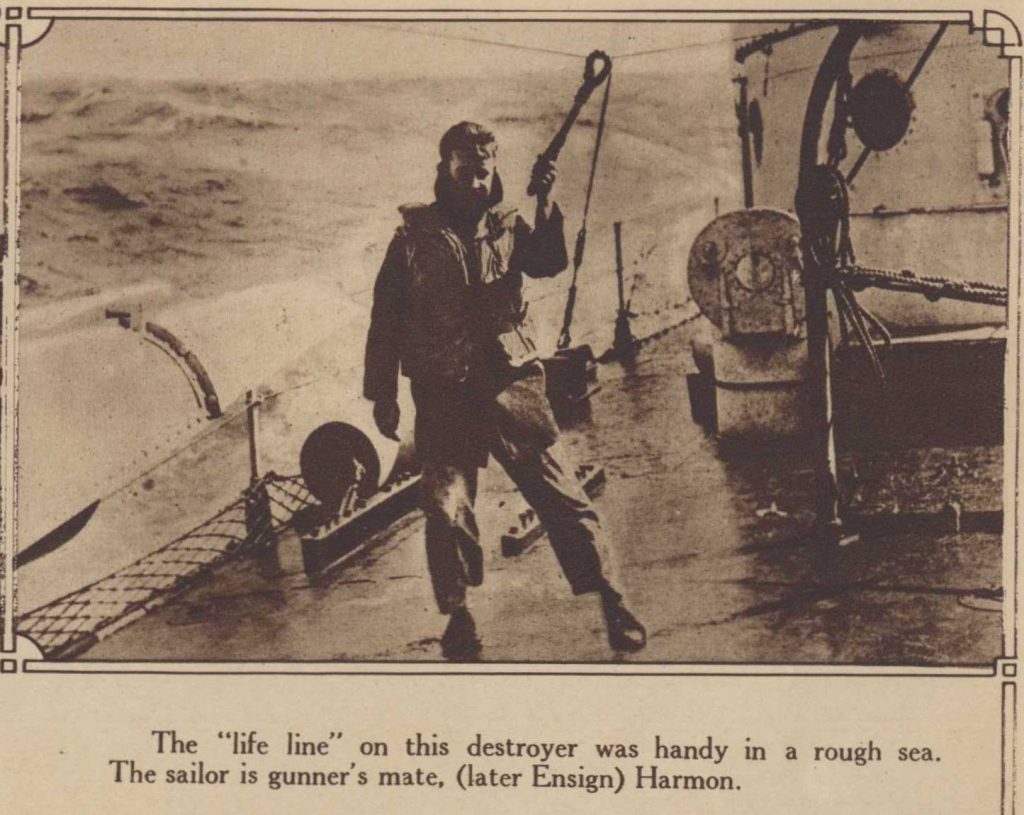

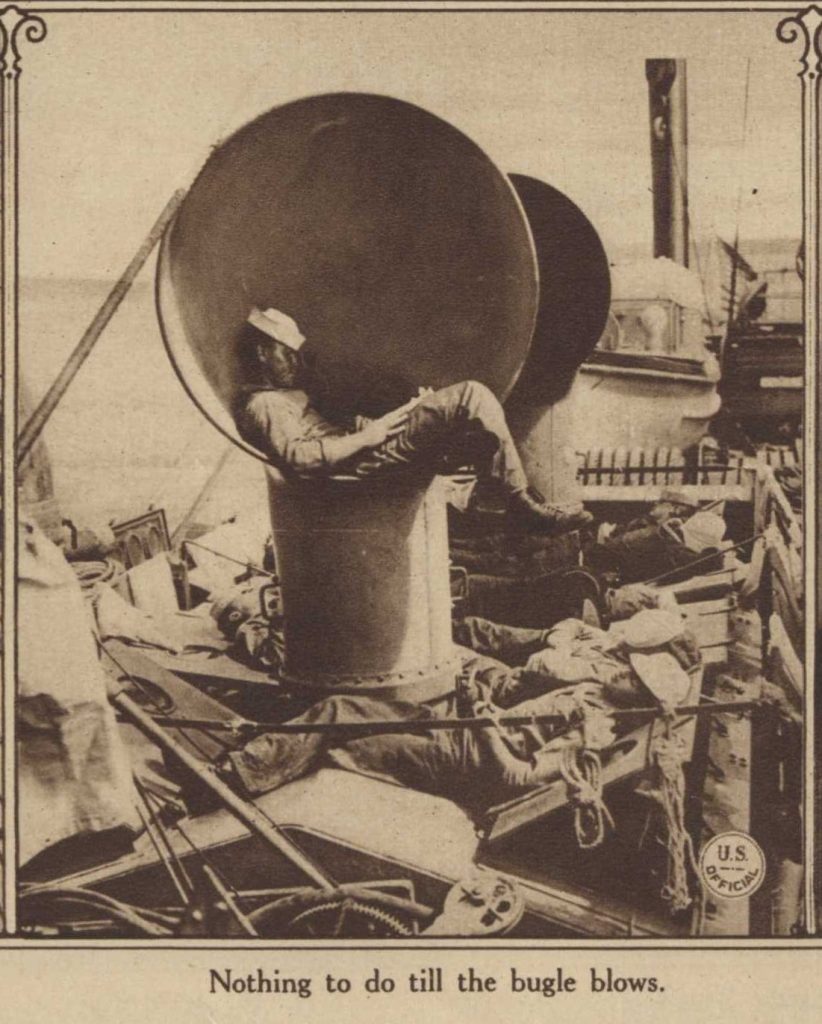

The U.S. Navy maintained three distinct classes of training facilities. The first type of facility was the Training Station. Training Stations were the oldest and most well-established bases. There were only four bases with this title: “Newport, Rhode Island; St. Helena (Norfolk), Virginia; Great Lakes, Illinois and Yerba Buena (San Francisco), California” (Besch 17). The second class was the Training Camp. During the war, all the American territories divided into eighteen different “districts.” A Training Camp would act as a sort of headquarters in districts one through thirteen. Districts one through thirteen trained recruits, while districts fourteen through eighteen “covered the offshore bases such as the Philippines, the Caribbean and Central America” (Besch 17). The training station and the training camp would operate in generally the same fashion, except in training where the “districts [were] to train reservists for service on vessels within the particular district. Most district fleets were composed of small patrol craft” (Besch 17). The last class of facility was a School. These schools trained men in specific jobs needed in the Navy, such as cooks or gunners’ mates (Besch 18). The length of training varied depending on the specific program the recruit was in, the job they were training for, and the need for new soldiers on active duty. Students in the Student Army Training Corps, which contained a Navy recruit department, enrolled in a “course of study compressing a four-year degree program into three with the twelve-month year being compressed into eight months” (Besch 187). Similarly, when the Navy needed new submarine-trained soldiers, their training was cut from six months to three (Besch 170). As for the creation and impact of the SATC Naval division, “[the] Committee on Education and Special Training of the War Department” created the SATC and allocated approximately 8% the estimated 150,000 eligible for the draft to the Navy (Besch 186). Training in the SATC officially began less than two months before the end of the war. As a result, “the SATC had virtually no effect on the course of the war and, if anything, a detrimental effect on the men and institutions where it operated” (Besch 192).

Preparedness

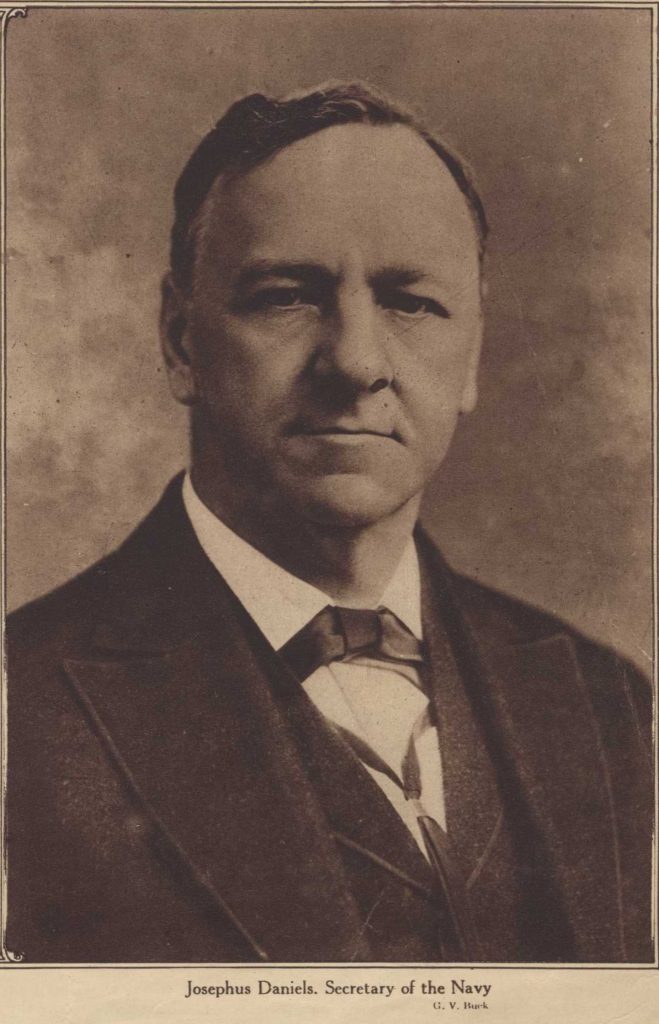

“My knowledge of machinery and battle-ships is so slight that I understood very little of operations or explanations” (Besch 1). Written on March 27, 1913, by the Secretary of the United States Navy, Josephus Daniels, this passage demonstrates how unlikely a choice Daniels was for his position. Receiving the position from President Woodrow Wilson for his campaign support, Daniels’ lack of nautical knowledge was only one of the factors making Wilson’s decision highly questionable. “What made Daniels an even more curious choice … was his outspoken pacifism” (Besch 2). Together, this would become a dangerous combination, which could have affected the outcome of the First World War. Before the United States entered the war, there were two general trains of thought on how to be prepared. “In Daniels’ view, preparedness meant a state of trained readiness on the part of existing personnel on active warships” (Besch 2). This meant that the Secretary of the Navy was apprehensive about hiring more seamen and constructing new ships while the country was on the precipice of war. However, there was another way of thinking that its proponents would go to great lengths to support. To “Franklin Roosevelt, preparedness meant having a naval force that would be able to defeat any enemy to come against it” (Besch 2). As a result, Admiral Bradley Fiske and Franklin Roosevelt, Assistant Secretary of the Navy, organized a demonstration in Chesapeake Bay in May of 1915. Led by Fiske, fueled by a long-standing rivalry between him and Daniels, “Fiske’s intention was not just to embarrass Daniels but to highlight what he saw as the path forward by creating the political preconditions for the secretary and Congress to increase naval funding” (Peeks 68). As a result, this war game was partially organized with a specific intention of proving the navy was unfit for active service. To achieve this, the red fleet, representing an invading force, was informed of the blue fleet, representing the America’s Navy’s, plans. In addition, the red fleet was also assigned significantly more ships to gather intelligence on the blue fleet. In the end, the red fleet won, “ostensibly pointing out the unpreparedness of the American navy” (Besch 3). Orchestrated surrounding the “Navy’s lack of small scout cruisers and large, fast battle cruisers,” the invading fleet, Red, had twenty scouts and four battle cruisers (Peeks 84). Meanwhile, the American fleet, Blue, had three scouts, two of which were acting as scouts, and no battle cruisers. Although premeditated, this defeat, in the eyes of Roosevelt, unequivocally proved the need for more supplies, among them ships and recruits. This exercise did not sway Daniels in his beliefs, as he would not authorize others to spend money “until well into 1917… even though the money was appropriated” (Besch 21). However, Congress was convinced of the need for a more balanced naval force. “The force structure gaps highlighted by the 1915 exercises successfully informed the landmark 1916 Naval Expansion Act, which provided for an unprecedented construction program” (Peeks 68). In the meantime, other officials took the problem of a lack of recruits into their own hands.

From 1913 to 1916, Rear Admiral Leigh Palmer was the personal secretary to Secretary Daniels. Following that, Palmer “Became chief of the Bureau of Navigation” (Besch 16). As the head of the bureau tasked with training most new recruits, Admiral Palmer was very familiar with the state of recruitment and how it would impact the United States Navy’s ability to effectively deploy troops upon entering the war. In fact, Admiral Palmer “made a forecast following the passage of the Naval Act of 1916 that manning the ships… as well as bringing current crews to full status would require an additional 950 regular officers, 1,600-1,700 reserve officers, 28,000 regular enlisted men and 23,000 reserves” (Besch 18). In efforts to fix this shortage of personnel, Palmer would continue to recruit men throughout the war, for regular enlistment or reserve, that could be convinced to sign up, despite being told repeatedly by his superior, Secretary of the Navy Daniels, to stop signing people to the Naval Reserve Service. “Daniels’ concern was that the reservists were signing up as Class Four reservists, which meant that they could be assigned only to coastal duty. Palmer’s idea was that it was better to have trained reservists, even if they were assigned to coastal duty, than no reservists at all” (Besch 20). Others, like Rear Admiral Josiah S. McKean, shared Palmer’s belief that recruiting was necessary to the operation of the U.S. Navy. “Chairman: ‘So that personnel was a vital question and the key to getting the Navy ready.’ McKean: ‘It was indeed. It is the only thing that puts life into the inanimate material’” (Besch 19). It is because of Admiral Palmer’s disobedience that the United States had sufficient soldiers to come to the aid of her allies on the water.

Vying for Naval Supremacy

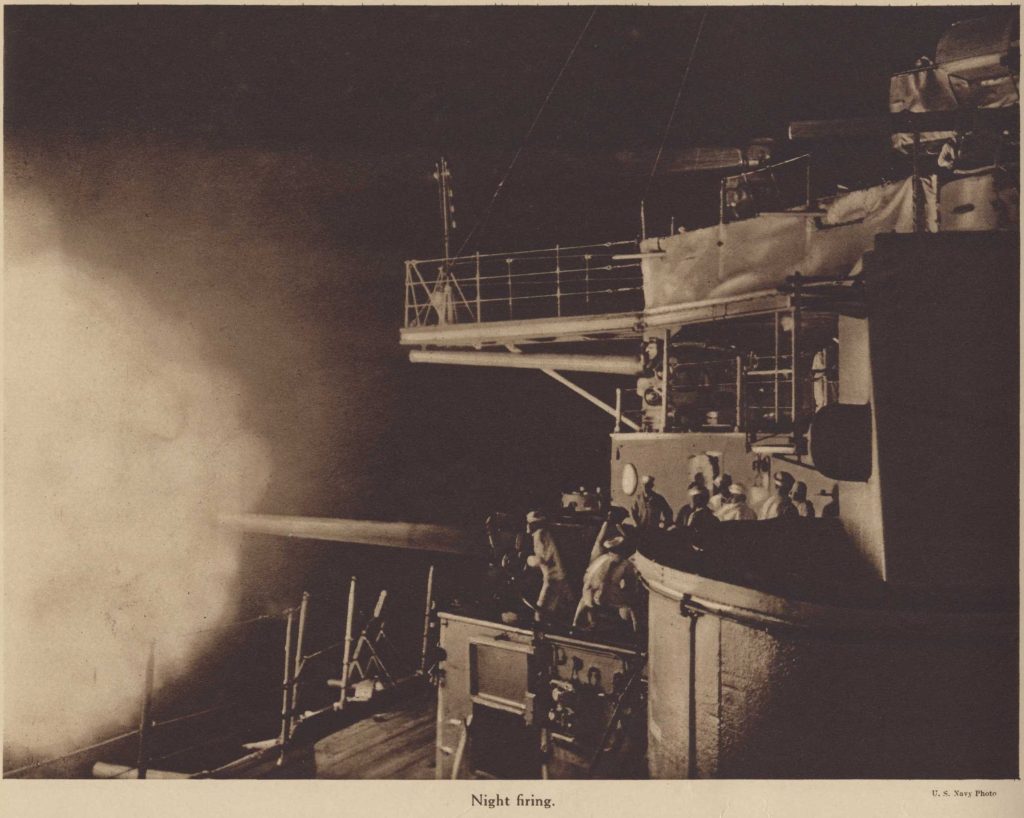

In the war the belligerents deployed battle cruisers armed with vastly different aiming methods. Both Germany and the United Kingdom extended ship gun barrels, which resulted in a loss of accuracy and made it harder for gunners to predict where a shell would land. To solve this problem, the Germans invented a machine that could account for the known and unknown variables of the firing ship and the opponent ship and use trigonometry to improve and adjust their aim. The British, on the other hand, made a highly complex mechanical system that “was ahead of its time; it relied on a multitude of flexible drives and bevelled gearing which must have produced small, but cumulative mechanical errors” (Warships 77). In fact, in the largest Naval battle of the war, the British had an accuracy of 2.75 per cent, landing 123 of 4480 total rounds, while the Germans were slightly more accurate, landing 122 of 3597 total rounds, or 3.39 per cent (Stille 72-73). As the United Kingdom and Germany continued to improve their aiming systems, Germany and the United States adopted different submarine strategies.

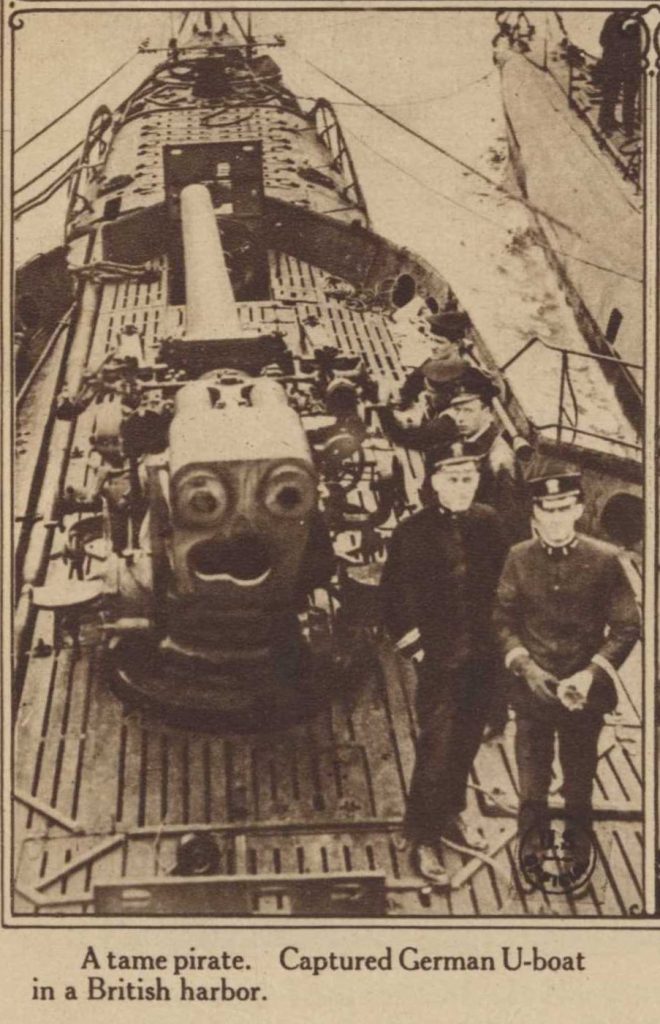

“Primitive submarines had been used in both the American Revolution and the Civil War” (Besch 168). Nevertheless, it was in World War One that the submarine gained strategic significance. The Germans were early proponents of the submarine, or U-boat, which they deployed in unrestricted submarine warfare. Despite their success with this tactic, the vessels were not stealthy. “The early U-boats had a great capacity for attracting attention to themselves, during daylight by the smoke from the exhausts of their Körting petrol engines, while at night these same exhausts gave forth brilliant flames, and at all times the noise of the engines served as a warning to any foe for miles around.” (Warships 19). In addition to these tells, some German submarines were even escorted out to sea for protection while they submerged “which took between five and seven minutes”, resulting in their position being exposed to enemy craft during this time (Warships 19). In general, the submarine was an effective weapon, but one that was dangerous for its operators. These were some of the reasons that the United States was skeptical about the use of submarines far from home soil. “Few envisioned the submarine as a deep-sea offensive weapon. Most naval planners, instead, viewed the submarine solely as a defensive weapon, for use in defending the major coastal ports against possible attack from enemy capital ships” (Besch 168-169). Regardless, the United Stated eventually joined Germany in the use of submarines as a common offensive weapon.

Importance of Navies

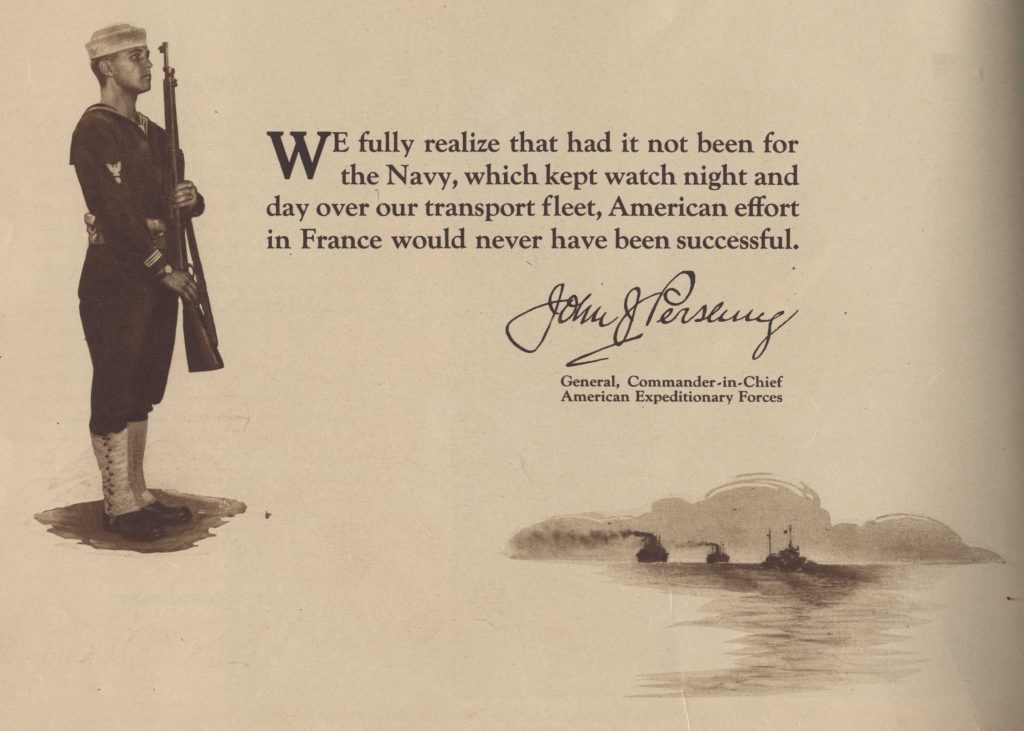

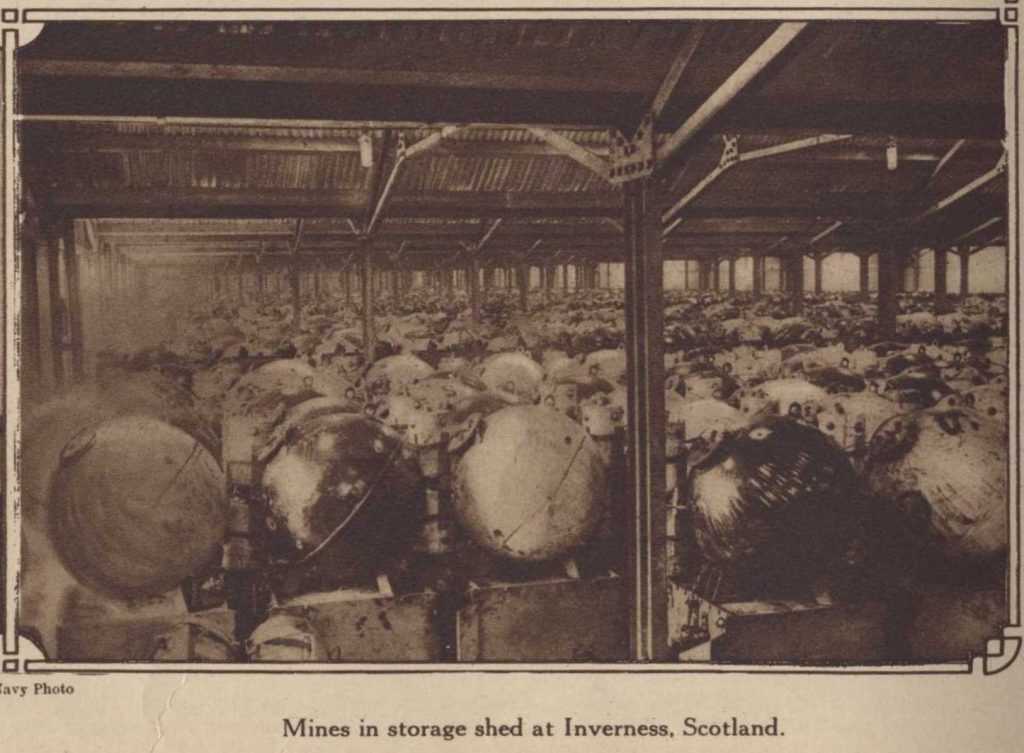

Navies were vital to keeping shipping lanes open for the transport of soldiers, supplies, and nurses. Mine-laying ships deployed mines to protect Western European waters, while dreadnoughts took center stage in some of the bloodiest battles of the war. Aviation was in its infancy and the best method of intercontinental travel was still the boat. This meant that ships were necessary for the transportation of government officials. This transportation was essential for Allied officials who congregated and negotiated the terms of the Central Powers’ surrender and the signing of the Treaty of Versailles. Fighting on a battlefield that covered most of the globe, the navies of the Great War have left a lasting impact on how we view, create, and use technology on the water, both in times of peace and war.