1914: Then Came Armageddon

Influenza 1918-1919

“They loaded them on trucks like cordwood”- Elmer Denzer

OH# 00302, Stories From the Front: In Their Own Words, Wisconsin Veterans Museum

Origins of Spanish Influenza

Nearing the end of the First World War, Spanish Influenza wreaked havoc across the globe. This strain of influenza has many origin stories, but as the name suggests, the most common was the infection originating in Spain. And like influenza, this misconception spread around the globe. For the counties actively participating in the war, their news was mostly dominated by the movement of their troops, outcomes of battles, and war bond advertisements. Unlike those countries, Spain was neutral. This resulted in, as doctor and author Thomas Helling called it, “freedom of the press produced honest and frank reporting of this new illness” (Helling, 271). Because Spain seemed to be the only country reporting on the flu, many countries began to believe that Spain was the first to encounter the illness and named it as such. The actual origin has been traced to the United States, and specifically to the area of Santa Fe, Haskell County, Kansas. In February of 1918, cases of a new illness remarkably similar to what would become the Spanish flu began to emerge. If it weren’t for the war, there was a chance that this illness would have died out, but with enlistments, men all throughout Kansas began traveling to Camp Funston for training. It’s in Camp Funston where history has designated Haskell Country resident, Private Albert Gitchell, army cook, as patient zero (Helling, 262). From here, the new disease spread with the troop movements until it was all over the United States. Eventually, it traveled with the troops overseas, where it would begin infecting people at the ports and spreading to the front. Growing to affect people all over the world, this was only the beginning of a second global tragedy, which would prove to be even more devastating to human life than the entirety of the First World War.

Influenza In Milwaukee

The trouble for Milwaukee began in Great Lakes, Illinois, at the Great Lakes Naval Training Station. On September 11th, 1918, the first cases of the flu were documented. Shortly, the infection had spread all over the camp. Unfortunately, this did not stop officials from granting furloughs. Upon returning home, these soldiers spread Influenza all over the Midwest (Abing, 145). By September 21st, 1918, it had officially reached Milwaukee (Abing, 146). Described by Milwaukee County Historical Society Archivist and author, Kevin J. Abing, the lack of protocols doctors had to follow didn’t aid in easing the spread either, as “doctors were not compelled by law to report influenza or pneumonia cases” (Abing, 146). This lack of protocols was not completely to blame. Milwaukeeans had been warned to limit contact with others and avoid large gatherings. For war bonds, however, this warning was ignored.

In the second year of American participation, companies and individuals continued to buy, and were pressured into buying, war bonds. Drives or parades to increase the sales of these bonds were not uncommon, and the 4th Liberty Loan Parade on September 27th, 1918, spread more than just enthusiasm. “Roughly 25,000 participants and thousands of spectators crammed along city streets provided the perfect breeding ground for the spread of deadly germs”. (Abing, 146). In the following days, the rate of infection exploded. Learning their lesson, the people of Milwaukee began to obey the recommendations of the Milwaukee Health Commissioner, George C. Ruhland. People began to understand the importance of quarantining, but the damage has been done. To add insult to injury, at this point in the war, many medical professionals had left to help injured soldiers in Europe. This resulted in a lack of hospitals and people to staff them when the flu hit.

To resolve this, Ruhland opened three emergency hospitals and reassigned the school nurses, doctors, and teachers to help patients and collect an accurate count of the number of infected (Influenza Encyclopedia). When new cases began to exceed one hundred per day, the first instance of this being in early October, city officials began to temporarily close common places of gathering. Some of the most common establishments closed were schools, theaters, and churches. Still in the throes of war, factories were one of the few establishments that remained open. However, this still left the city’s workforce at risk. With a dangerous illness spreading and people in isolation, the Milwaukee branch of the Wisconsin State Board of Health anticipated that some citizens might spread worrying rumors, such as false information about the infection. Shippenburg University History Professor Steven Burg notes that to keep Milwaukeeans from going into a frenzy, and to inform them of important health information, “health department officials met with the city’s newspaper editors, all of whom agreed to help by not publishing stories that might create a panic and by printing educational stories and editorials urging compliance with the influenza campaign” (Burg, 48).

Despite the speed with which the infection spread, Milwaukee suffered fewer deaths than most other large cities. Ruhland “attributed this commendable record to three factors: 1) the early decision to close schools, businesses, etc., 2) cooperation that the health department received from the Common Council and other organizations and 3) willingness of Milwaukee citizens to comply with the orders” (Abing 150). Combined, these actions helped to keep the death toll in Milwaukee to a minimum with a mortality rate of “2.91 per thousand, compared with a national average of 4.39 per thousand” (Burg, 41).

“Sure was a queer Sunday. Not a machine on the street because of the gasoline conservation order. All places of amusement closed because of the ‘Flu’. And so we just stayed home. Red & knit all day. Couldn’t even go to church because they were closed because of the ‘Flu’.” – Rayline Oestreich diary entry, October 13th, 1918

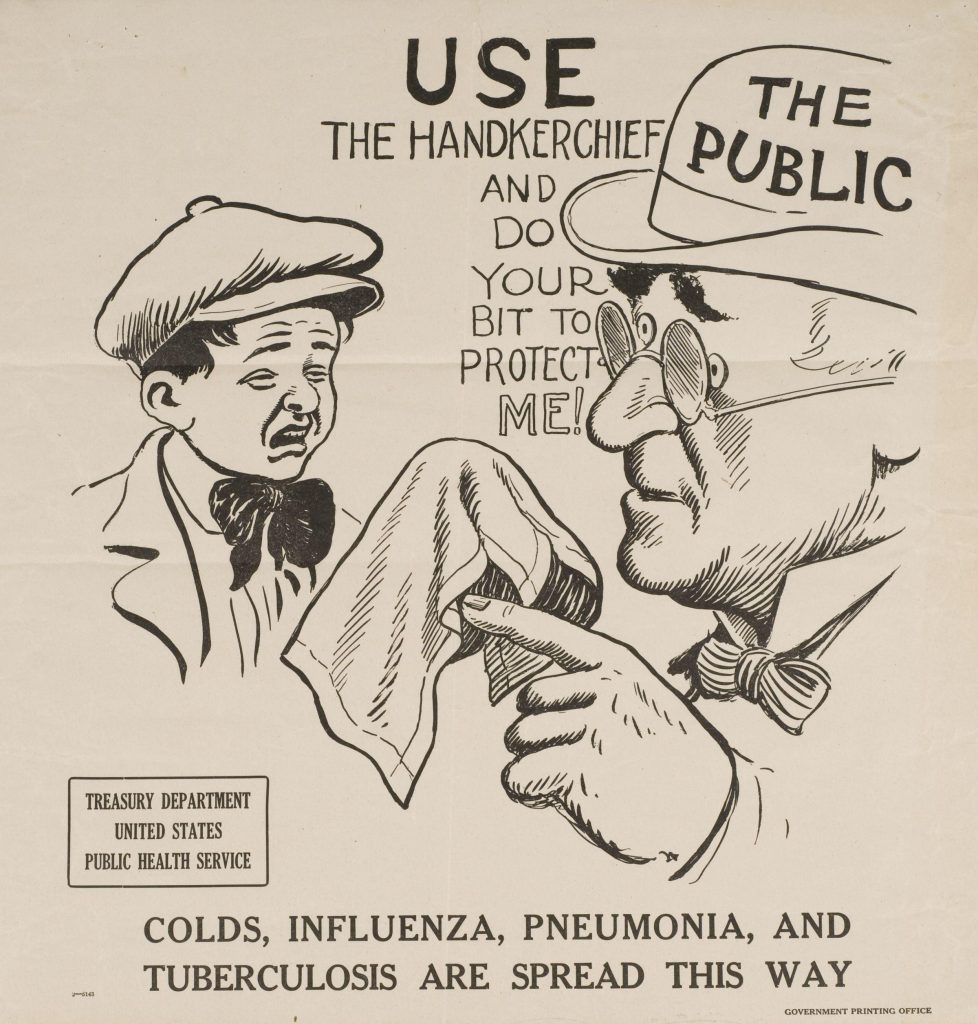

How people tried to prevent the spread

On the United States home front, Influenza was raging in major cities and small towns alike. The U.S. government recognized the problem and began to create public health reports to inform the public on how to prevent infection. One report mentioned avoiding crowds, wearing masks around those who were sick, and encouraging proper ventilation of homes. The report went so far as to discourage reckless spitting, coughing, and sneezing. According to Rupert Blue, the United States Surgeon General during the epidemic, “the most dangerous form of human contact in the presence of epidemic influenza is… that with coughers and sneezers. Coughing and sneezing, except behind a handkerchief, is as great a sanitary offense as promiscuous spitting” (Epidemic, 4). Spitting was such an egregious offense at this time that in some cities, fines and court appearances were imposed on those caught in the act (Abing, 150). Many Americans took this advice to heart and began to do things, such as wearing masks in public, to protect themselves and their families. If one were to catch the deadly virus, the pamphlets also had recommendations on how to treat patients. “The treatment is symptomatic. On account of cardiac weakness, rest in bed should be prolonged after defervescence in proportion to the severity of the case. Attention to cleanliness of the mouth, adequate ventilation, avoidance of exposure to cold, and isolation from those who may be carriers of virulent pneumococci and streptococci are measures advisable to prevent complications” (Epidemic, 4). Despite doctors’ and nurses’ best efforts, those who were infected often deteriorated into an extremely painful state. “So little could be done other than cooling sponges, expectorants, and maybe touches of opium” (Helling, 277). With the pandemic beginning so late in the war, cities like Milwaukee, Wisconsin, that were already trying to make do and hold out for the end of the war, faced a new challenge: balancing what was needed for the war effort and what must be done to save lives.

“‘Wir athmen dadurch eban so anstandslos wie eine Dame, die auf der Straße den Schleier trägt’ (‘We breathe as easily as a lady wearing a veil on the street’)”-Johann von Mikulicz-Radecki (Inventor of gauze mask)

Why Influenza Was So Deadly

Although “influenza is an ancient disease first described by Hippocrates in 412 BC” (Webster, 52), each strain is slightly different than the last, and all have the potential to be deadly. The 1918-1919 Flu is a prime example of this. With an incubation time of two to three days, the virus has just enough time to spread to other hosts before rendering its victim noticeably ill (Helling, 266). This fast incubation time can be seen through the exponential rate at which patients were admitted to hospitals and sick bays. In Milwaukee, Wisconsin, “the number of cases reported daily exploded from 69 on October 5 to 214 on October 7 to 340 on October 8 and to 453 on October 11” (Abing, 146-7). Following the onset of symptoms was an array of ghastly ailments that, in some cases, would drown a patient on land. The sickness began relatively mild with “chills followed by high fever, body aches and runny eyes” (Abing, 145). If the patient was lucky, this was the worst it would get. For the unlucky, “twenty percent of those infected developed pneumonia, and nearly half of those cases developed heliotrope cyanosis in which the victim’s lungs filled with a thick, blackish liquid that turned their skin black-blue. Those cases were usually fatal within 48 hours.” (Abing, 145).

What happened worldwide

With the war raging and America entering the conflict, troop movements were the perfect highways on which the Spanish Influenza spread. Medical Historian K. David Patterson and Professor of Public Health Science Gerald F. Pyle state that “the spring and fall illustrated… that the world had become a single epidemiological unit. Aided by the greatly enhanced pace and volume of human movement, pandemic influenza spread with remarkable speed and affected almost every inhabited place on the planet” (Patterson, 20). This movement, while in the United States, helped to kickstart the population base from which the entire world would soon be infected and eventually led to “between 20 percent and 40 percent of American military Personnel” contracting the infection at one point or another (Fargey, 26).

The spring wave or first wave brought the illness to the most populated centers of the globe. Unfortunately, as horrific as the spring wave was, the second, or fall, wave caused the majority of deaths from the Influenza virus. It cemented the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic in history as the deadliest modern pandemic. The second wave likely began in August in France and exited the country through the ports at Brest. The next known locations of infection were Boston, Massachusetts, and Freetown, Sierra Leone, which are both home to other ports (Geography, 8). By January 1919, the second wave had fully enveloped the globe (Geography, 11). It was during this second, more prominent, wave that people began to note differences in symptoms based on location. In the United States, some noticed that victims were more likely to be constipated, whereas in Spain, stomach issues were common (Epidemic, 3). With time, another strange pattern of the flu began to emerge. Like other viruses, Influenza infects people of all ages, races, and genders. Interestingly, instead of infecting the commonly at-risk groups, young children and the elderly, the 1918-1919 influenza tended to infect young adults (Trilla, 1). In Spain, for example, Professor of Preventive Medicine and Public Health Antoni Trilla claims, “mortality rates were higher among persons aged <1 year and among those aged 25-29 years” (Trilla, 5). With the third wave came even more confusion. In the winter of 1919, a third wave broke out in the Northern hemisphere and caused people to begin asking questions – namely, why did it end? Scientists, historians, immunologists, and epidemiologists would go on to wonder if the merciful end of the pandemic was a result of sudden herd immunity, an increase in antibodies, a mutation of the virus, or any number of other explanations (Helling, 279). Unfortunately, it seems unlikely we will even know the reason for the end of the Spanish Influenza; however, arguably more important is the search for an accurate number of those who died.

“I have been having extraordinary attacks of fever, with such general neuralgia that I can only manage to exist in an artificial condition of tottering weakness with the help of aspirin and pyramidon…. I’m simply collapsing”. – German officer Rudolf Binding’s journal entry from mid-August 1918.

The Death Toll

Today, it is generally accepted that 50 million people died of the Spanish Influenza, but this number is likely to be a stepping stone on the journey to a more realistic estimate. Since the Influenza pandemic of 1918-1919, there have been only a handful of academics willing to take on the daunting challenge of creating an accurate estimate of the global death toll. The first estimate offered in 1927 by Edwin Oakes Jordan, an American bacteriologist and Public Health Scientist working out of Chicago, Illinois, was around 21.6 million (Patterson, 19). Be that as it may, like all other estimates, there are inconsistencies in its calculations- namely, incorrect and inconsistent information. Not all flu deaths were recorded, and if flu patients developed a secondary illness, their death may not have been attributed to the flu. For example, anyone who died of pneumonia, cyanosis, encephalitis lethargica, or any other complication that can be a result of influenza, as late as 1928, may not have been counted as a death from the flu. This leads to the possibility of millions of unknown cases. On the other hand, there were no specific parameters for how a military camp was to count their flu cases. As mentioned in her article “The Deadliest Enemy: The U.S. Army and Influenza, 1918-1919,” Military historian Kathleen M. Fargey explains that “Different statistics cover different time periods: some encompass only the height of the epidemic at a particular location… Statistics also reflect different circumstances: some include a camp’s total population; others measure only those who became ill or those admitted to a particular hospital” (Fargey, 32). This means that some camps may have included the people who died of the flu out of the total population, while other camps may have reported those who died out of all of the sick, or those who died in a specific hospital. All of this results in the potential for the percentage representing the chance of death at every camp, base, or training station to be calculated with different parameters. As a result, mortality rates can not be implicitly trusted. Still, these rates came from some level of reporting. In some cases, like many camps for the American Expeditionary Forces, statistics may not have been reported at all. “Although about 15,849 members of the AEF died of influenza and pneumonia in Europe, it seems that the Army surgeon general did not collect or publish disease statistics for individual camps or locations there as it did for Army camps in the U.S.” (Fargey, 32). Figuring in this inconsistency, other authors have been getting closer to identifying the real impact the flu had. According to a paper written in 1991, using conservative estimates, only the fall wave amounted to 25 million. Using the high end of the same parameters results in an estimate of 40 million deaths. Noting this, Patterson and Pyle, the researchers who compiled this information, suggest that 30 million would be the most probable total for the death toll for the fall wave alone.

Keeping in mind the two other waves and straggling pockets of disease that would continue to pop up around the globe for years to come, it is easier to see where the generally accepted 50 million came from (Patterson, 19).In addition to this, a more recent study published in 2002 and authored by Johnson, an employee at the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare in Sydney, NSW, AU, and Mueller, published in the Bulletin of the History of Medicine, recognized a pattern in the scholarship attempting to discover the true death toll. With every paper published, the estimate increases. As the next set of researchers attempting to look at global mortality of the Spanish Influenza since Patterson and Plyle, their findings held true when Johnson and Mueller settled on an estimate of 50 million to as many as 100 million deaths. (Johnson, 115). With continued work focusing on discovering more accurate small-scale death tolls, future attempts at uncovering the global death toll will also be more accurate. Regardless of how much work is put into this cause, we will never know how many people really died from the most destructive pandemic in modern history.