1914: Then Came Armageddon

The Battle of Jutland

“I can hardly even now describe the thrill we all felt– the Grand Fleet had arrived”.

Warships and Sea Battles of World War I, Page 83

Introduction

The British Navy had a reputation as one of the most effective navies of the modern era. Aiding its vast colonization efforts, the British Royal Navy, to many, was akin to an unstoppable force of nature. British subjects held a similar idea: “to most British readers… whenever the Royal Navy encountered an enemy, the foreigners must inevitably go to the bottom” (Massie 661). Any force willing to go against the Royal Navy, specifically the Grand Fleet, must have been large, powerful, well-built, and well-organized. On May 31st, 1916, the German High Seas Fleet, two-thirds the size of the British, took on the gargantuan task and engaged in what would be the largest Naval battle of the First World War. Because both knew the Grand Fleet was much larger, both sides assumed the battle would result in a decisive British victory. However, the outcome resulted in initial reports that “gave a shocking impression of mishap, even disaster” (Massie 661).

Why the North Sea was Important

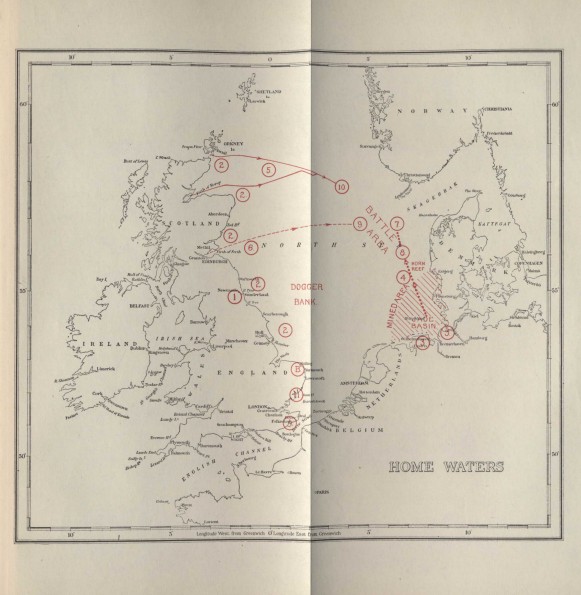

The Battle of Jutland took place in the North Sea off the peninsula of Denmark. The North Sea was a critical location for the British to control because of the shipping lanes that ran through the area. Early in the war, the UK and France set up a Naval blockade against Germany, making resources scarce on the home front. The Germans wanted to reciprocate. Should the Germans have been able to capture these lanes, they could have turned the tide and created a crisis on the Western Front, as the British depended on shipping lanes in the North Sea for foreign aid and transportation of troops. With Germany isolated on the continent, they were able to trade with neutral countries and deliver supplies to their troops. In addition, a lack of provisions would eventually starve Britain and her soldiers, allowing the German military to advance. As a result, the blockade and subsequent command of the North Sea were integral to the success of the war. In fact, “the whole basic British strategy… was to subject Germany to a distant blockade… This could only be achieved by British command of the sea” (Warships 103). It was both sides’ desire for control and, subsequently, sufficient resources that led to the Battle of Jutland.

Admirals’ Goals

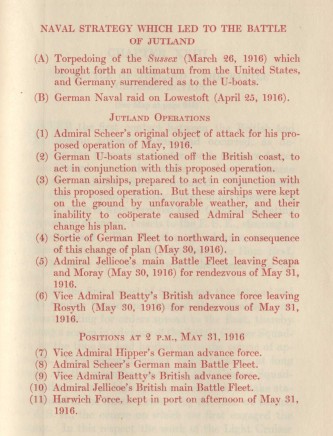

The beginning of the war was relatively calm for the British Royal Navy. With little for the sailors to do, Admiral Sir John Jellicoe instituted exercises and training drills designed to keep the fleet ready for any conflict. While the navy were performing “occasional sweeps…, tactical exercises, target practice…, and coal[ing] ships” (Warships 73), Jellicoe was exercising his “rocklike refusal to be stampeded into any adventures that would threaten the British command of the North Sea” (Warships 73). Should Jellicoe engage in a battle and lose, he could be held responsible if the Germans instituted a British blockade. However, Jellicoe’s ability to refuse confrontation ended when the German Admiral Pohl, who was reluctant to challenge the Grand Fleet, was replaced due to a terminal cancer diagnosis. His replacement, former Vice-Admiral Reinhard Scheer, was intent on weakening the Grand Fleet. Scheer’s strategy was to separate a small part of the fleet until he could actively engage it in battle; meanwhile, his U-boats and sea mines would occupy the rest of the fleet until a “full scale encounter between the two opposing fleets would not be too hazardous an adventure” (Warships 73). To achieve this, Scheer orchestrated multiple encounters between the fleets. His first attempt, on February 10th, and his second, three weeks later, were both failures (Warships 73). These instances did inspire the British to have raids of their own, but, all British and German attempts would fail until the Germans’ fourth and final plan, which led to the Battle of the Jutland.

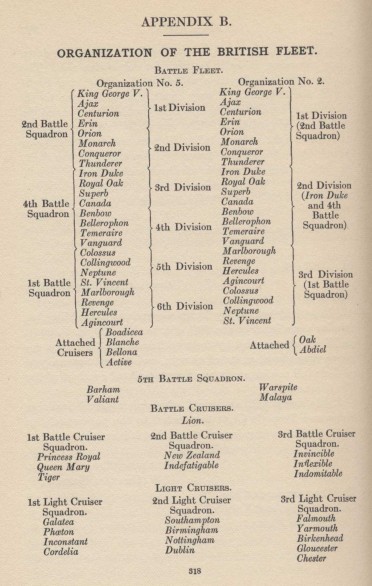

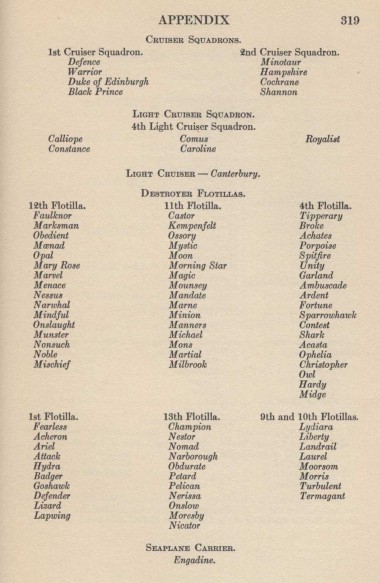

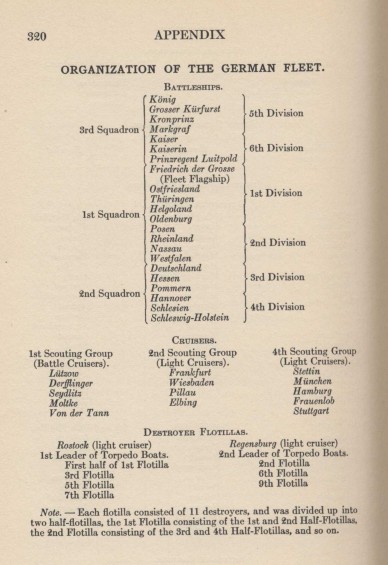

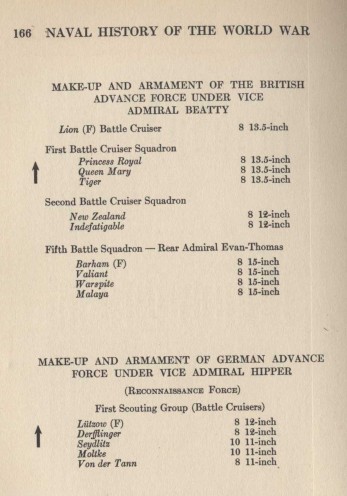

Power of the Fleets

The Grand Fleet had more ships at its disposal than the High Seas Fleet. At the battle, the Grand fleet had one hundred and fifty-one ships, while the Germans had ninety-nine (Imperial). Britain’s large and technologically advanced fleet facilitated overconfidence within the Royal Navy. “One officer… confided to his diary afterwards, [t]he only question was how long it would take to put all five German ships on the bottom” (Warships 79). Although the British had technologically superior ships, as seen in their more complex aiming system, this battle would violently reveal the Grand Fleet’s shortcomings.

This does not mean that the Germans had an easy fight ahead of them. Compared to the British fleet, the German fleet had a shorter firing range and lower top speed. Yet, the German ships had an advantage over the British in armor thickness and shell construction. “The upper deck of his [Jellicoe’s] flagship was protected by 1½-1¾ inches of steel armor. But Scheer’s flagship, Friedrich der Grosse, boasted 2-2½ inches” (Hough 272). As a result, a hit was more dangerous for the British. The Germans were able to take more shells and remain afloat because of Britain’s relatively ineffective shells. “British shells were filled with lyddite. The combination of lyddite and a too sensitive fuse caused the shells to burst on oblique impact, so that the whole force of the explosion was outside the German protective armour” ( Warships 106). Although the British shells were comparatively weak, Scheer would still be outmatched if an encounter resulted in a full-scale battle, due to the British having more experience with Naval battles. With this in mind, Scheer began formulating a plan that would level the playing field.

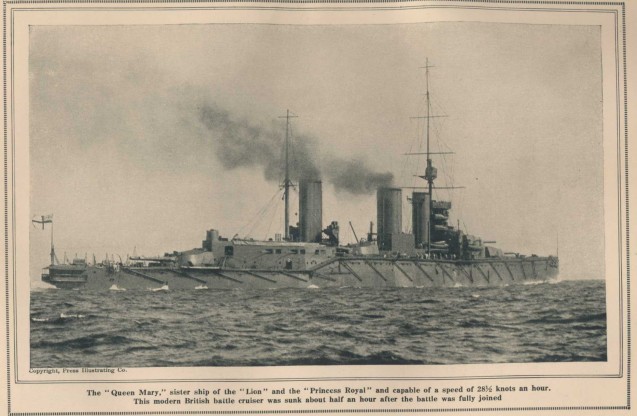

The Battle

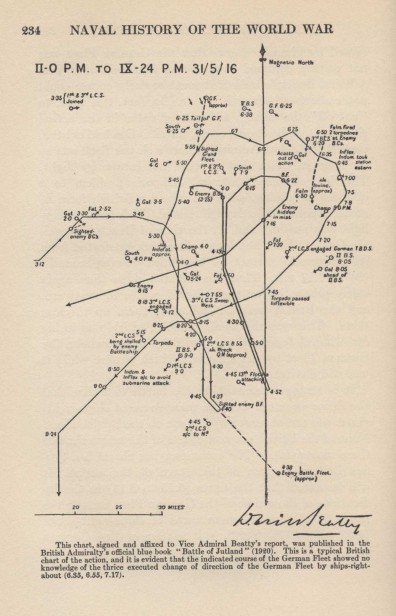

The battle commenced on May 31st at 1415 hours, when unbeknownst to either fleet, at only about sixteen miles apart, both fleets’ light cruisers saw a ship in the distance. This vessel was a “neutral merchantman, the Danish steamer N.J. Fjord” (Warships 78). Both approaching the steamer to investigate, at 1420, the HMS Galatea raised the flag indicating “‘Enemy in sight’” (Warships 78). Soon after, Vice Admiral Sir David Beatty raised his signal to the rest of his ships, but “the signal was made by flags and these, together with the Lion’s funnel smoke, were blown by the light westerly wind… so that the signal was not picked up by the 5th Battle Squadron”. Comprised of four Queen Elizabeth-level battleships, the 5th Battle Squadron missed the signal, making Beatty’s forces even easier prey for German Vice Admiral Franz Hipper. This was a dangerous situation for the British, considering that both the British and German fleets were divided into two different forces; however, with the British 5th Battle Squadron ten miles away, the Grand Fleet was split into three (Warships 78). The subsequent ninety minutes were relatively uneventful until 1547/1548 hours. The German Gun range was 19,700 yards, while the British range was reported to be 24,000. The British range was over-exaggerated by 2,000 yards but was still able to fire against the Germans before the High Seas Fleet could close the distance. However, when the range reached 16,000 yards, Beatty’s Flag Captain, Chatfield, was forced to give the orders to open fire (Warships 79).

When the battle started, Jellicoe and the rest of the Grand Fleet were seventy miles away from Beatty. Because of this, Jellicoe only arrived at the battle at 1740 hours (Warships 83). Jellicoe’s arrival at the battle was aided by Beatty leading Scheer and Hipper North, to the rest of the Grand Fleet. Hipper and Scheer, believing they were heading to a base, seemed to forget that all British bases were to the east, allowing Beatty to lead the High Seas Fleet directly to Jellicoe, initiating the full-scale encounter Scheer so desperately wanted to avoid (Warships 83).

Although this was not the only full-scale encounter of the battle, another resulted from Scheer attempting to escape under the cover of night. Suspecting Scheer would try this, Jellicoe sent ships to cover both of the High Seas Fleets’ potential escape routes. However, this section of the battle would be slightly less violent, due to the night making it difficult to discern which ship was in which fleet. This, in turn, resulted in offensive attacks slowing at night. Action picking up slightly again at dawn, the battle ended at 0324 hours when Scheer gave the final signal for the High Seas Fleet to return to port.

The Outcome

Over a century later, historians are still debating which fleet won. Casualties and loss of ships point to a German victory. British casualties were undoubtedly higher than the Germans’. Although the Germans’ initial reporting was conservative, once corrected, the British still lost more men during the battle. Estimates for British casualties range from 6,768 (Massie 665) to 6,945, and it is widely agreed upon that German casualties total 3,058 (Stille 72). This disparity is attributed to the prevalence of flashes in the Grand fleet. The British, in the Battle of Jutland, had five ships blow up due to flashes, specifically due to Britain’s habit of storing the propellant in silk bags near magazines, and leaving the doors open to the magazine stores to increase the rate of firing. (King 156) If hit, the propellant would create a distinctive flash that would ignite the magazines, potentially causing a massive explosion. Extremely harmful to the Grand fleet, the High Seas Fleet had learned the importance of safety measures to protect from flashes at a previous battle, Dogger Bank. “Thus, at Jutland, powder exploded and fires wiped out turret crews on Derfflinger and other ships, but… the ships did not blow up” (Massie 667). It is because of these flashes that we can see the number of casualties mirrored in the tonnage of ships lost, where the British lost 111,000 tons and the Germans lost 62,000 tons. (Warships 103).

However, these statistics are only one way of measuring success in a battle. In terms of goals achieved, and when the fleets were ready to sail again, the British prevailed. “[Jellicoe’s] primary object was to retain command of the sea, and his second was to annihilate the High Seas Fleet” (Warships 103). After the battle, the British did “retain command of the sea”. It is neutralization that can be argued. Post battle, each of the Admirals gave a report on when their fleet could sail again. “Jellicoe was able to signal the Admiralty at 2145 hours on June 2 that the Grand Fleet was at four hours’ notice for steam and ready for action. Scheer, in his report to the Kaiser, gave the middle of August” (Warships 106). Considering the Grand Fleet was larger, the damage done to the fleet was important but not debilitating, whereas the damage done to the High Seas Fleet put it out of commission for at least two months, and it would mostly stay in port for the rest of the war. In this way, it could be said that the Grand Fleet effectively neutralized the High Seas Fleet.

Looking at Scheer’s goals, he attempted “to isolate a portion of the Grand Fleet and to bring it to action against superior force, but he was determined at all costs to avoid action with the fleet as a whole” (Warships 103). Initially, Scheer managed to make contact with a subsection of the Grand Fleet; however, by ignoring reports that a force was seen closer than he estimated Jellicoe to be, little of the battle was fought before the Grand Fleet reunited. Therefore, Scheer barely achieved his first goal and failed his second. Because of this, depending on what each historian values most as deciding factors in naval battles, it can be argued that either side won, or that the battle was a draw. This is seen directly following the battle, when ignoring the context and focusing on the tonnage of ships lost and casualties, the Germans spun the battle as a victory. Soon after, the Germans’ reports were published in Great Britain. “London newsboys were on the streets shouting, ‘Great naval disaster! Five British battleships lost!’… Overseas,… headlines read, ‘Britain Defeated at Sea!’ ‘British Losses Great!’ ‘British Fleet Almost Annihilated!’” (Massie 660). Naturally, these headlines shocked British citizens. Winston Churchill, the Prime Minister, sought to calm the public. To do so, he put the statistics of the battle in greater context. “He brought out the crucial fact that the High Seas Fleet had escaped destruction only by flight. He stressed that sea control depended on dreadnought battleships and that British supremacy in this respect was unimpaired” (Massie 662). He also stated that the loss of British ships “was regrettable, but far from crippling” (Massie 662).

In hindsight, we can see the Germans excluded key context of the battle to frame the outcome as a victory, whereas the British leaned heavily on context to discredit the German reports. Churchill would continue to write on this topic, specifically in his multivolume work The World Crisis. Volume three, published in 1927, has two chapters dedicated to the battle. Within these chapters, Churchill discusses Jellicoe’s reasons for trying to avoid confrontation, stating “All he [Jellicoe] knew was that a complete victory would not improve decisively an already favorable naval situation, and that a total defeat would lose the war” (Churchill 105). Or, as Churchill also said, “Jellicoe was the only man on either side who could lose the war in an afternoon” (King 154). Combined, these two quotes paint a picture of the British naval position in mid-1916. Addressing Jellicoe as the only man who could lose the war, while taking into account that a victory would not improve their situation, points to the British navy occupying the best possible position in the North Sea for the allies. This also speaks to the importance of the shipping lanes running through said sea and the potential consequences if they had been captured.

Due to the discrepancies in reports, it was not long before the Germans realized they would have to publish a more accurate account of the battle. “On June 7, the German Naval Staff was forced to reveal its additional losses” (Massie 659). Scheer soon realized that a fleet battle with the British would not yield his desired outcome. Still hopeful to slowly weaken the British forces, “Scheer told the emperor that ‘a victorious end to the war within a reasonable time can only be achieved through the defeat of British economic life– that is, by using U-boats against British trade” (Massie 659). Nevertheless, Scheer still had a fleet of ships under his command, which he attempted to use three more times before the war ended. Failing to resurrect his Sunderland operation, the High Seas Fleet was brought back to port, and “there they lay, rusting and crewed by mutineers, when the war ended on November 11, 1918” (Massie 684).

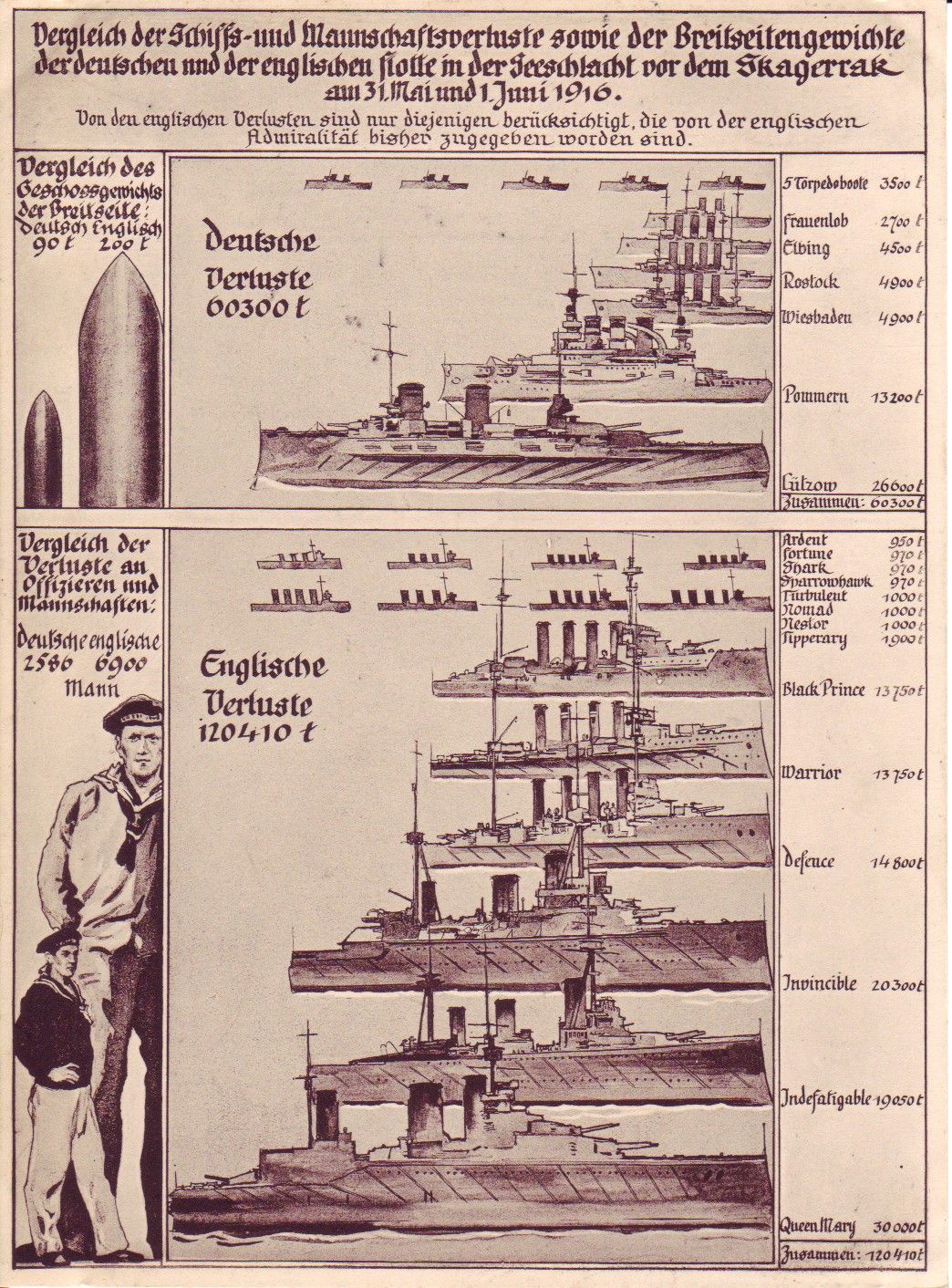

Poster Translation:

Comparison of the sailor and crew losses as well as the broadside weights of the German and English fleets in the naval battle off the Jutland on May 31 and June 1, 1916.

Of the English losses, only those that have so far been admitted by the English Admiralty are taken into account.

Comparison of the total weight of broadside. German 90 tons. English 200 tons.

Comparison of officer and enlisted losses: German 2586. English 6900. Total losses: 9,486.

German losses: 60,300 tons.

5 Torpedo boats 3,500 tons

Frauenlob 2,700 tons

Elbing 4,500 tons

Rostock 4,900 tons

Wiesbaden 4,900 tons

Pommern 13,200 tons

Lützow 26,600 tons

Together 63,000 tons

English losses: 120,410 tons.

Ardent 950 tons

Fortune 970 tons

Shark 970 tons

Sparrowhawk 970 tons

Turbulent 1,000 tons

Nomad 1,000 tons

Nester 1,000 tons

Tipperary 1,900 tons

Black Prince 13,750 tons

Warrior 13,750 tons

Defence 14,800 tons

Invincible 20,300 tons

Indefatigable 19,050 tons

Queen Mary 30,000 tons

Together 120,410 tons

Conclusion

For such a complex battle, historians generally agree that neither the British nor the Germans won outright. However, the Battle of Jutland was still a major turning point in the war and the history of Naval warfare as we know it. Still studied today, primarily as a result of its unexpected results, the unprecedented confrontation was both a beginning and an end. The battle was the beginning of a new era of naval technology. “Germany’s naval technology was proved by Jutland to be superior to Britain’s. Her ships were stronger, her guns more accurate, her ordnance more destructive” (Keegan 175). The battles consisting of sails, wooden ships, and cannon balls were officially relegated to the past in favor of aiming systems, boiler rooms, and anti-aircraft guns. Additionally, the battle was also the end of Britain’s unparalleled naval supremacy. No longer was British victory a guarantee. Fundamentally changing the way naval battles were fought and thought of, the Battle of Jutland may not have a clear winner, but it has left a lasting legacy on the history of the First World War and of the British Empire.