Website Search

Find information on spaces, staff, and services.

Find information on spaces, staff, and services.

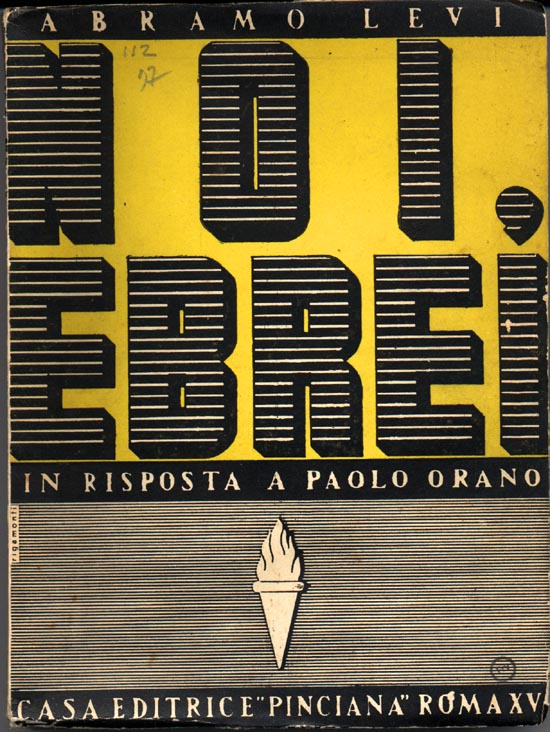

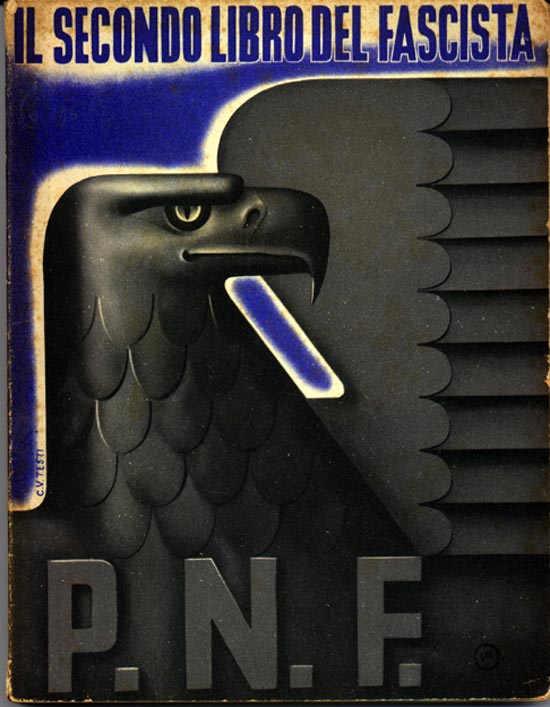

The following citations are for the images shown above, left to right, illustrating books and other works included in the exhibit “Italian Life Under Fascism” in the Department of Special Collections in 1998.

The following items were part of the original exhibit in the Department of Special Collections but are not pictured above.